A Year on Earth: Why the Planet Has Seasons

Why Earth Has Seasons

Earth takes, 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 46 seconds to complete a full orbit around the Sun. This journey is called a year. At the same time, the planet spins once every 23 hours and 56 minutes. This is known as a day. To keep things tidy for calendars and clocks, years are rounded down to 365 days, and days are rounded up to 24 hours. The missing time gets added back later, but we'll come back to that!

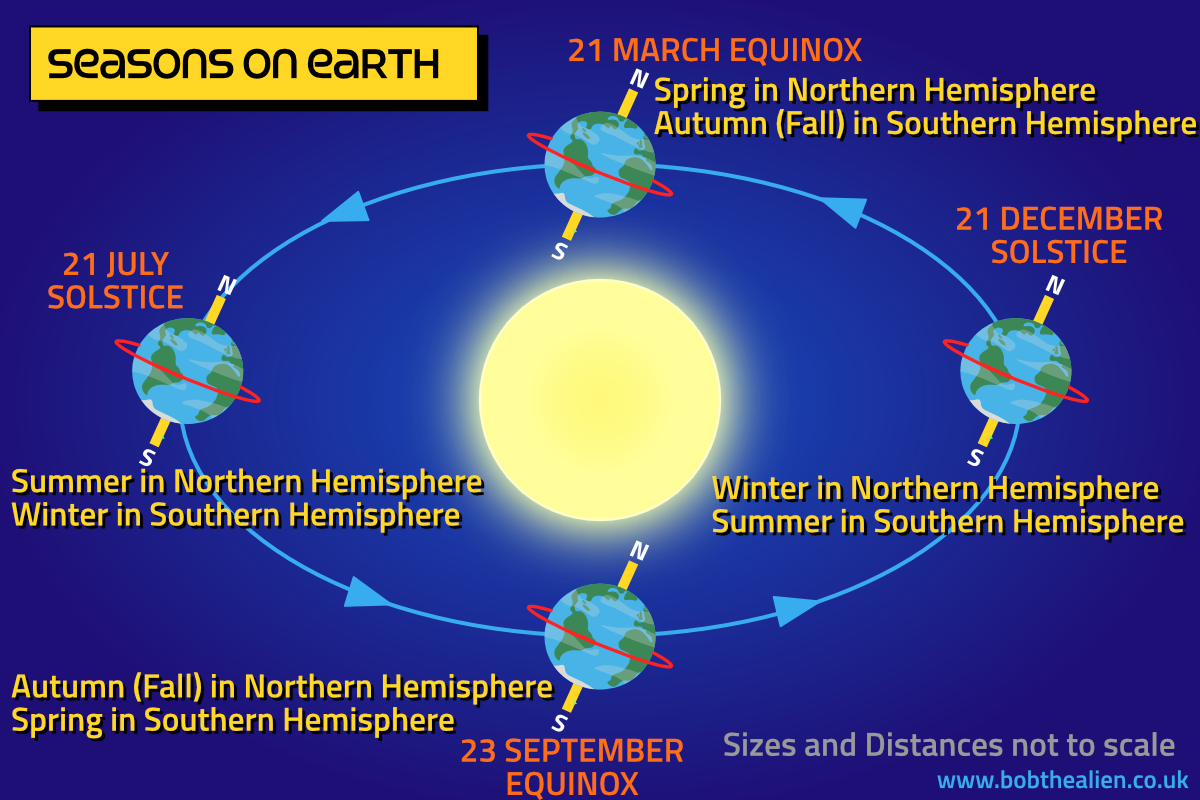

As Earth travels around the Sun, it passes through changing seasons. These shifts aren't caused by how far the planet is from the Sun, but by something more subtle and clever: Earth's tilt.

Earth is tilted at an angle of about 23.4 degrees. This tilt stays the same as the planet orbits the Sun, which means different parts of Earth get different amounts of sunlight at different times of the year. When one half of the planet (a hemisphere) is tilted towards the Sun, it gets more direct sunlight and longer days - hello, summer! When it’s tilted away, the sunlight is weaker, the days are shorter, and temperatures drop. That’s winter.

The way Earth's tilt affects the planet depends on where you are and where Earth is in its journey around the Sun. The poles are always cold and have constant sunlight or none at all, the equator is always warm, but can be either wet or dry. And the areas in between go through a whole range of seasons over the course of 365 days.

The Four Seasons

Unless you live at the equator or near the poles, your year is likely divided into four seasons: spring, summer, autumn (fall), and winter. Each has its own feel. Spring brings longer days and new growth. Summer is warm (or hot!) with the longest days. Autumn cools things down, leaves fall, and animals start preparing for winter. Winter is colder, darker, and quieter, with many plants dormant and animals either hibernating or migrating. These seasonal changes are especially noticeable in places further from the equator but not too close to the poles - places where the tilt of the planet has the most visible effect.

Seasons at the Equator - Wet or Dry

If you live near the equator, things are a little different. This part of the planet gets fairly direct sunlight all year round, so temperatures stay warm -often hot - no matter the month. Instead of four distinct seasons, equatorial regions usually have just two: wet and dry. The wet season brings lots of rain and lush greenery; the dry season brings, well, not much - mostly sunshine and dryness!

While the temperature stays fairly consistent throughout the year, rainfall can vary a lot depending on the time of year and the region's local climate. Some areas, like rainforests, get soaked regularly. Others, like nearby deserts, stay mostly dry year-round despite being close to the equator.

Seasons at the Poles - Endless Day and Endless Night

At the very top and bottom of the planet, seasons aren't about warm or cold - it's pretty cold all year round. What really changes is the light.

For several months, the Sun doesn’t set at all. This is known as polar day, when it’s light even in the middle of the night. Then comes polar night, where the Sun doesn’t rise for months and everything is plunged into darkness. These light extremes are caused by Earth’s tilt. As the planet orbits the Sun, each pole takes turns being tilted towards it (summer) or away from it (winter).

With no true day or night during these periods, life near the poles has to adapt. In Antarctica, for example, male penguins spend the long, frozen winter huddled together to stay warm - and to keep their eggs safe. Meanwhile, their partners are off at sea, tracking down food. Come summer, the Sun finally rises again, and the whole colony springs into life and action.

So rather than four neat seasons, the poles experience just two extremes: months of daylight followed by months of darkness.

Four key moments in Earth’s orbit help divide the year into seasons. These are known as solstices and equinoxes, and they’re all about how much sunlight different parts of the planet receive on those days.

- Equinoxes occur when day and night are roughly the same length, as the Sun sits directly above the equator.

- Solstices are when the difference is most extreme, either the longest day or the longest night of the year. The word "Solstice" comes from the Latin soltitium, meaning 'Sun stands still' - because that's what it appears to do in the sky.

These events happen at the same time worldwide, but their meaning flips depending on which hemisphere you’re in:

| Approx. Date | Northern Hemisphere | Southern Hemisphere |

|---|---|---|

| March 21 | Vernal Equinox (Spring) | Autumnal Equinox (Autumn) |

| June 21 | Summer Solstice (Summer) | Winter Solstice (Winter) |

| September 23 | Autumnal Equinox (Autumn) | Vernal Equinox (Spring) |

| December 21 | Winter Solstice (Winter) | Summer Solstice (Summer) |

These moments don’t just kick off the seasons, they affect everything from daylight hours to temperature and even the behaviour of plants and animals.

Earth's Orbit - Not a Perfect Circle

Earth doesn’t orbit the Sun in a perfect circle. Its path is elliptical, meaning the planet is slightly closer to the Sun at some points than at others.

- Closest to the Sun (perihelion): Early January

- Furthest from the Sun (aphelion): Early July

Surprisingly, distance from the Sun doesn't cause the seasons. The difference between perihelion and aphelion - about 5 million kilometres - isn't enough to dramatically affect Earth's temperature. It's still all about the tilt.

That said, the elliptical orbit does play a subtle role in affecting the seasons:

- Southern Hemisphere summers tend to be shorter but hotter

- Southern Hemisphere winters can be harsher, as they happen when Earth is furthest from the Sun.

Earth isn’t the only world with seasons. Any planet with a tilted axis experiences them, but how those seasons play out can be very different. Here are a couple of examples in the Solar System:

Mars has a tilt of about 25 degrees - similar to Earth - so it goes through spring, summer, autumn, and winter too. But with a longer orbit, its seasons last twice as long. Since there's no known life on Mars, seasonal changes aren't about flowers blooming, leaves falling, or animals coming and going (unless they are there and hiding really well!). Instead, Mars' seasons are marked by polar ice caps shrinking and growing, and planet-wide dust storms that often stir up during the southern summer, when the planet is closest to the Sun.

Uranus, much further out, is tilted at 98 degrees, almost as if it's toppled over. It orbits the Sun on its side, giving rise to extreme seasons where parts of the planet can experience decades of daylight or darkness.

Earth’s orbit doesn’t divide the year into four equal seasons. Because the planet speeds up and slows down slightly as it moves around the Sun, the lengths of the seasons vary.

Here’s how they break down in each hemisphere:

| Dates (about) | Northern Hemisphere | Southern Hemisphere | Average Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 March – 20 June | Spring | Autumn | 92 days |

| 21 June – 22 September | Summer | Winter | 94 days |

| 23 September – 20 December | Autumn | Spring | 89 days |

| 21 December – 20 March | Winter | Summer | 90 days (91 in leap years) |

Leap Years

Way back at the start of this page, we mentioned that Earth’s year is actually longer than 365 days and its days are slightly shorter than 24 hours, but they're rounded down and up to keep calendars and clocks simple. Every four years, an extra day - 29th February - is added to keep the calendar in sync. That’s a leap year, and that one extra day causes winter to be just a little longer.